Everyone agrees that the United Kingdom’s asylum system is broken. In this briefing we will take a look at the whole of the asylum process, from the numbers claiming asylum to the decision-making process, the cost of the system, the volume and quality of decisions, the outcomes of appeals, the use of detention and the number of removals. The information is drawn mainly from the quarterly immigration statistics and transparency data for the year ended March 2023, the most recent available at the time of writing. Some of the figures are drawn from statistics relating to the Illegal Migration Bill.

The picture the data presents is of a system that has been overwhelmed. Not by new arrivals but by mismanagement. The people arriving to claim asylum are overwhelmingly refugees and they will, eventually, build new lives for themselves in this country. But they must endure bureaucratic purgatory first, seemingly to cleanse them of the supposed sin of irregular arrival. Waiting times for a decision run to years, during which time these refugees are forbidden from work, and forced to endure destitution-level support and temporary accommodation. As well as being bad for the refugees, it is causes an unnecessary charge on the public purse. And then, at the end of the process, despite all the tough posturing by the Home Secretary, almost no-one is removed anyway.

The time periods for some of the charts differ. The longest possible range has been used where provided in the data series.

Asylum arrivals

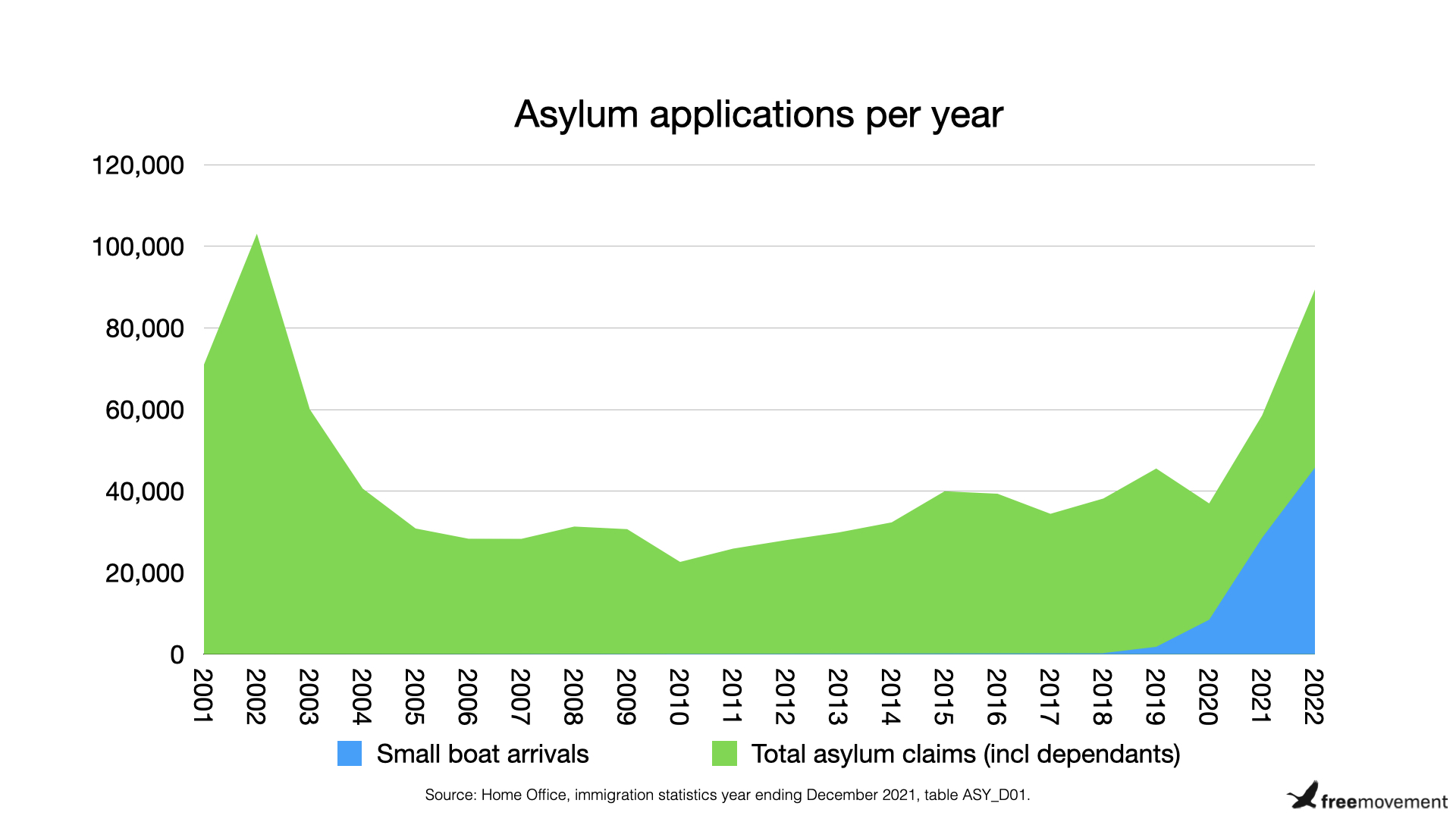

Following a significant peak in 2002, the number of asylum applications made in the United Kingdom was fairly stable between 2005 and 2020. The Syrian refugee crisis beginning in 2014 caused a slight rise in overall numbers.

The number of asylum applications increased significantly in 2021 and again in 2022, however. This was largely due to increasing numbers of arrival by means of small boats.

The shrinking area of green for 2020 and 2021 on the chart reflects the fact that the increase in small boat arrivals in large part represented a change of route by asylum seekers. Previously, lorries had been the principal means of entry to claim asylum.

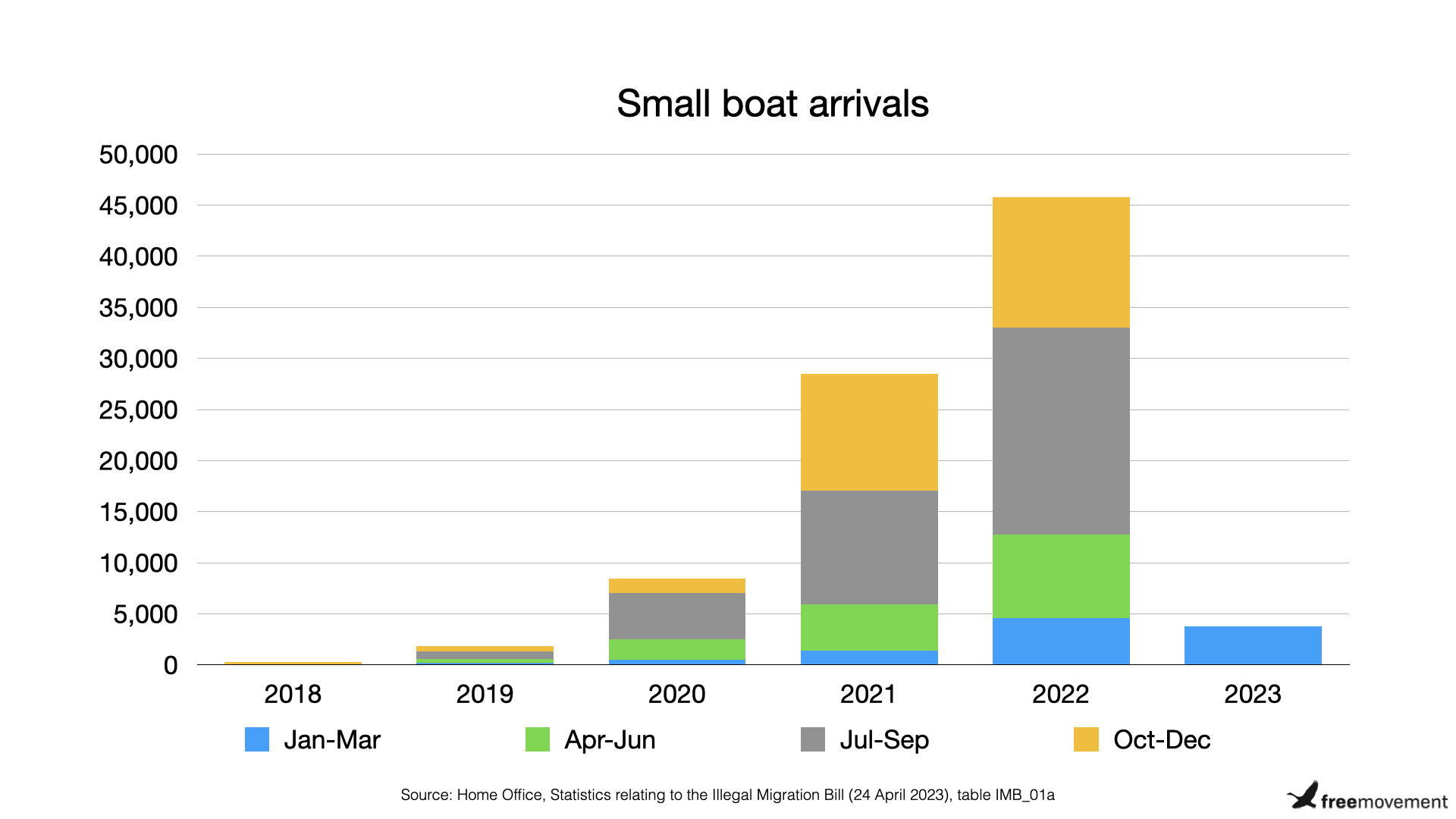

The number of small boat arrivals can be seen to have increased sharply from nowhere in 2018. The following chart shows overall numbers and also gives you an idea of arrivals by quarter. You can see that arrivals in the first quarter of 2023 are actually down a little compared to the first quarter of 2022.

The top six nationalities entering by small boat in the first quarter of 2022 were Afghan (909), Indian (675), Iranian (524), Iraqi (345), Syrian (286) and Eritrean (232), five out of six of whom have a high chance of being granted asylum (see below).

Asylum backlog

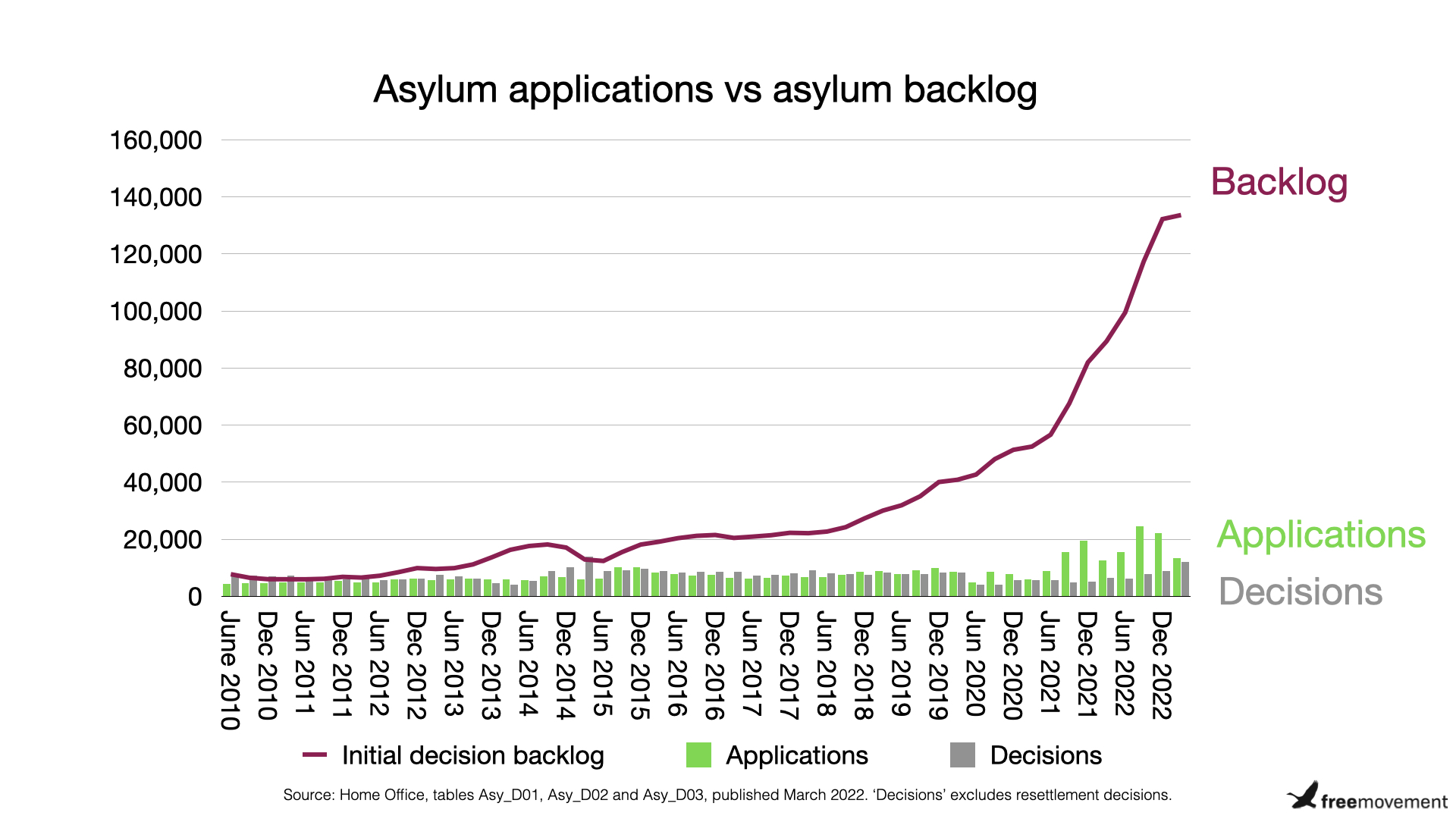

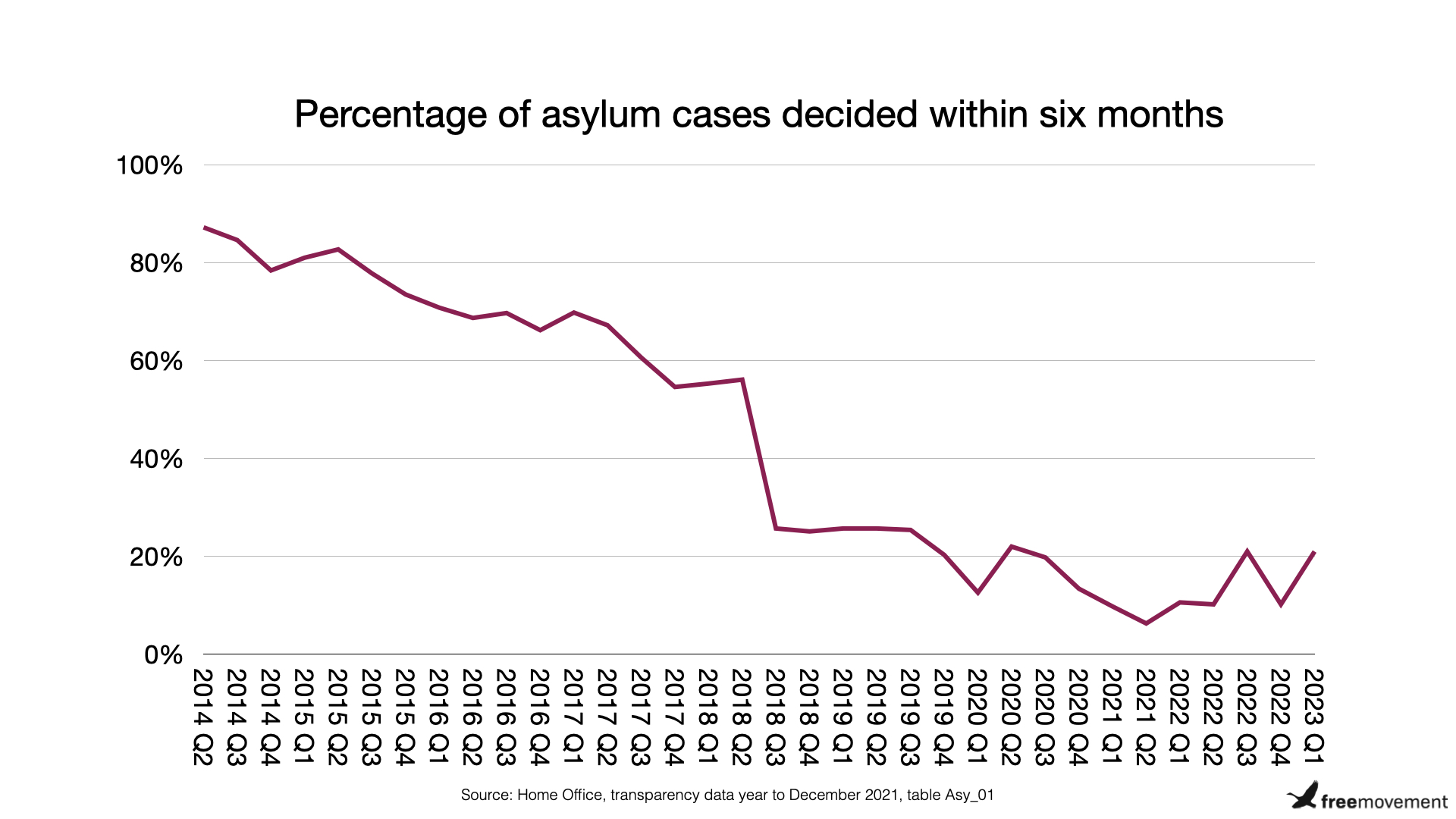

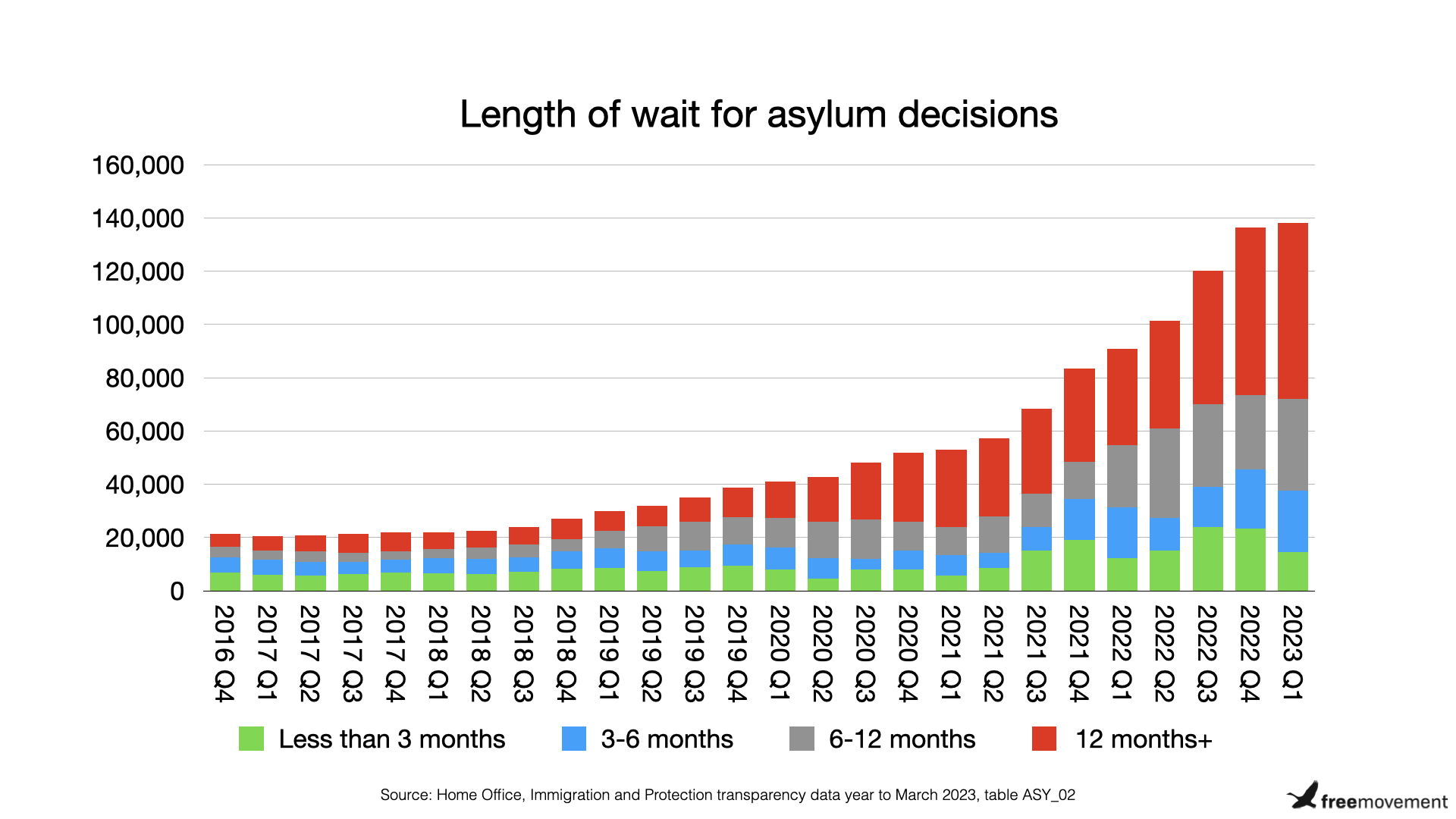

Arguably the stand out problem of the asylum system today is the time it takes for decisions to be made. This is a recent development. Unlike small boat arrivals, it lies entirely within the control of the Home Office.

If we plot arrivals against backlog and decisions we can see that the growth in the backlog, which really begins in the middle of 2018, considerably pre-dates the steep increase in arrivals in 2021 and 2022.

We can see that change in 2018 when the percentage of asylum cases decided within six months suddenly plummeted.

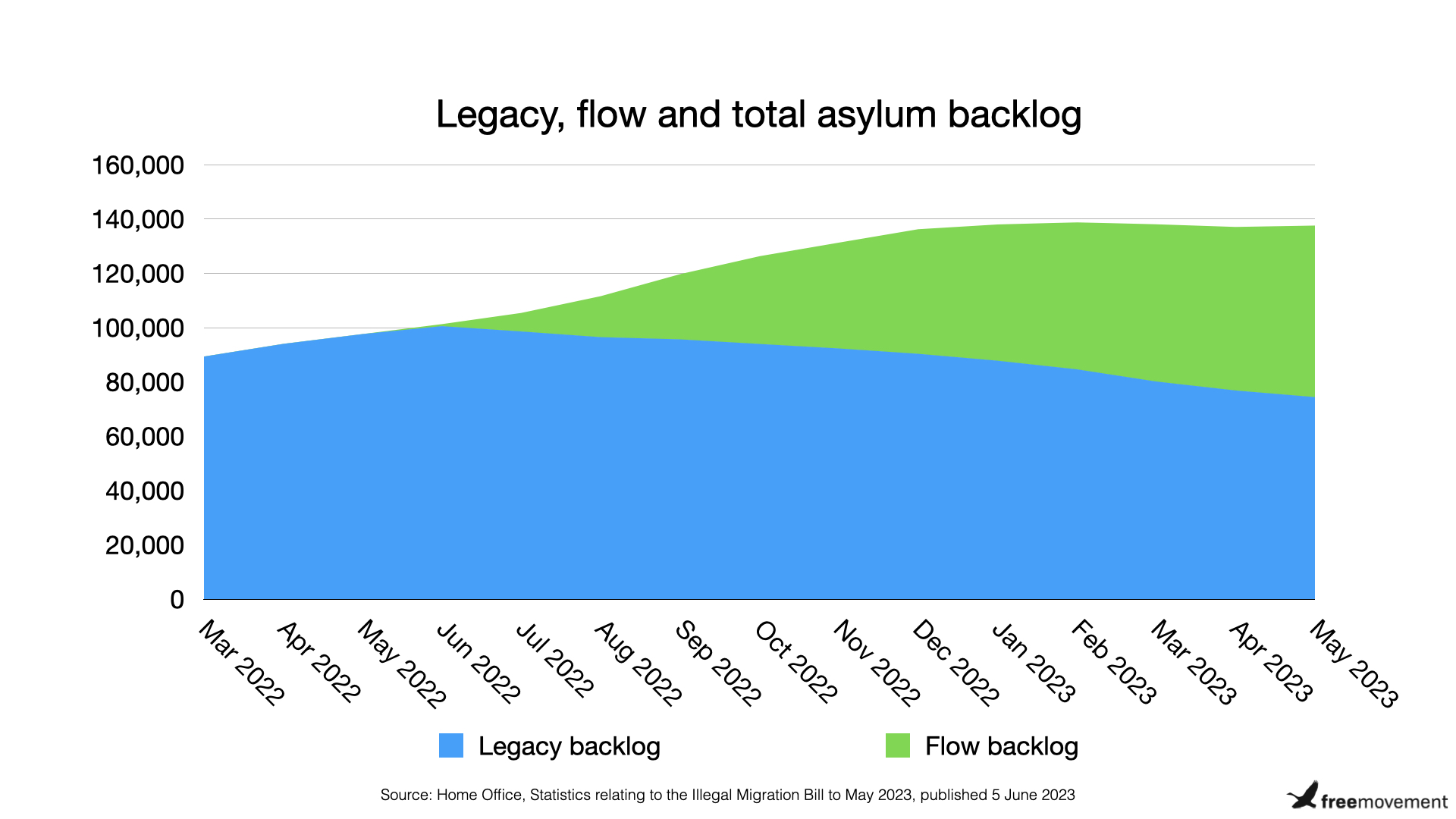

The backlog has started, finally, to stabilise, though. It has even started to fall a little, according to figures to May 2023.

At this point, though, there are tens of thousands of refugees who have been waiting for longer than a year for an initial decision. This is really expensive because they are not allowed to work, and so have to be supported by the government. Because the backlog was allowed to grow, the Home Office ran out of ordinary asylum accommodation long ago and has had to resort to using hotels. The international aid budget has been plundered in order to fund this.

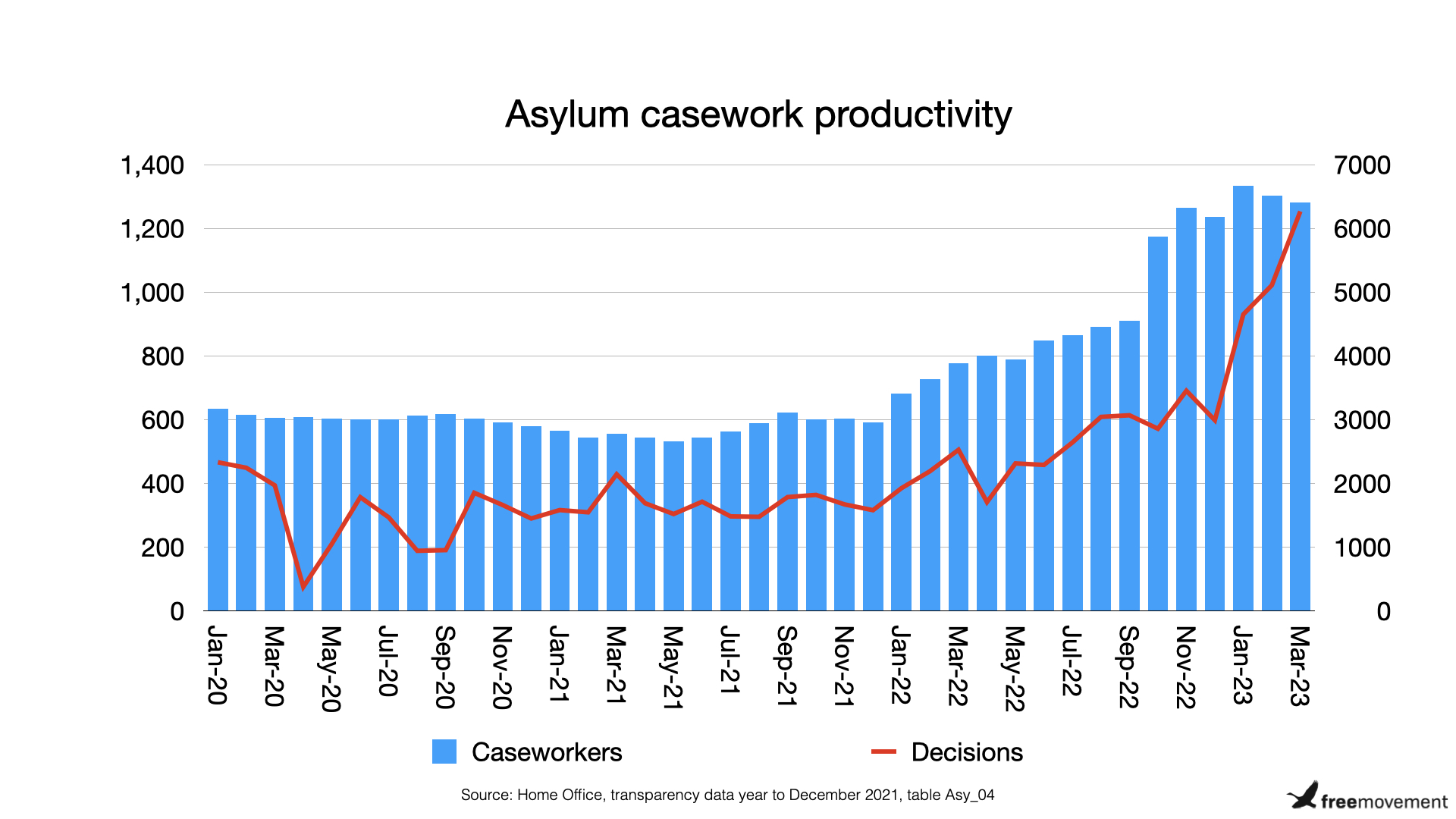

To deal with the backlog, the government decided to recruit more officials to decide asylum claims. On the face of it the number of decisions has finally started to rise rapidly. This looks like good news at first glance.

We’d expect there to be a lag between the recruitment of new caseworkers and an increase in decision making. But it looks like the recruitment drive for new caseworkers has stalled; numbers of caseworkers are actually falling again. Braverman had already said she planned to have 1,300 caseworkers in place by March 2023, which was more or less managed. But Sunak then pledged in December 2022 to double the number then in place, which would mean reaching a total 2,400 caseworkers. The government is nowhere near managing to recruit that many and they do not seem to be able to hang on to those they have recruited.

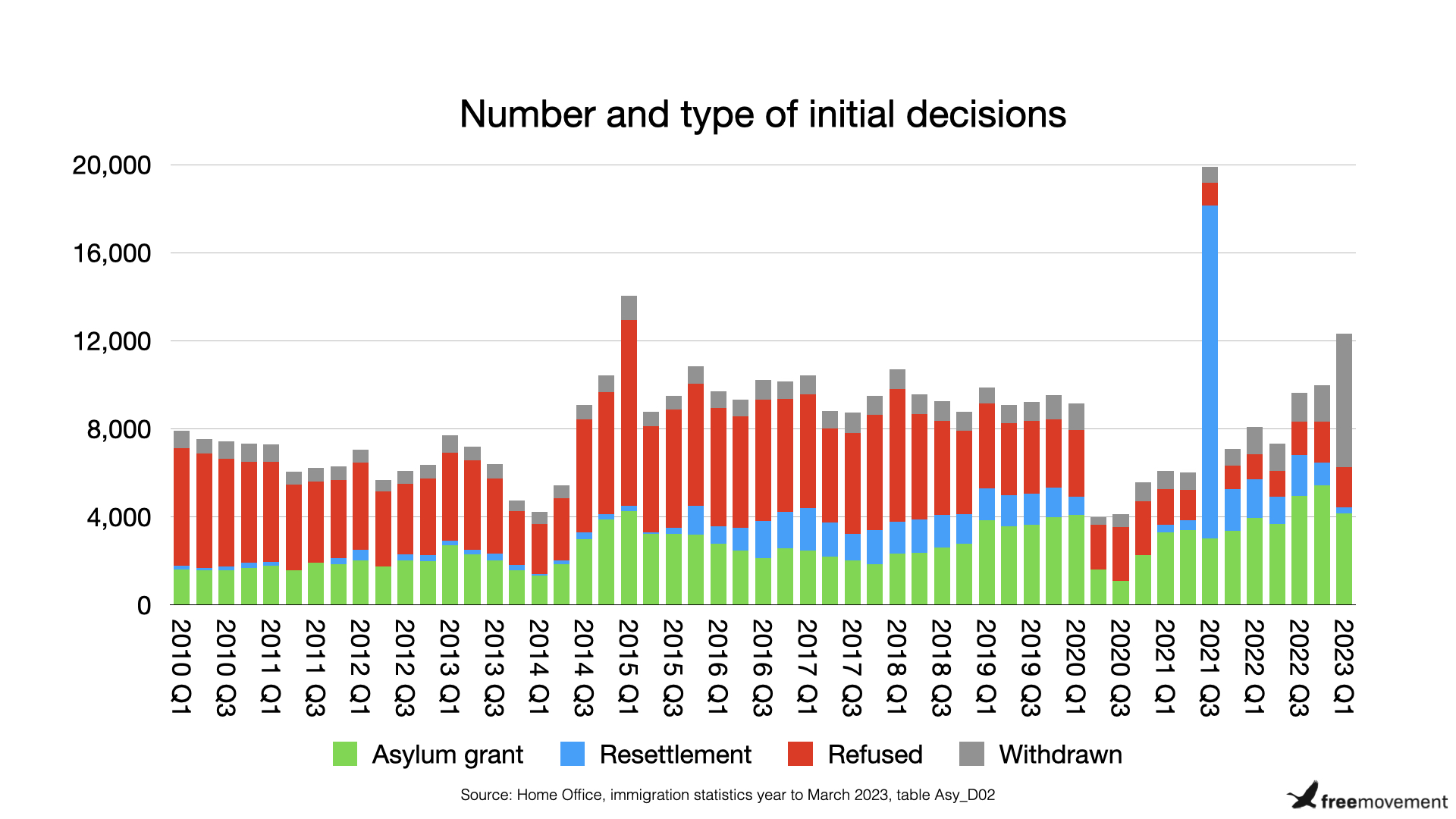

Further, it turns out the most recent figures on decision-making are distorted by a huge increase in withdrawals of asylum claims, mainly by Albanian nationals. Of 6,068 asylum withdrawals in the first quarter of 2023, 4,386 of them — almost three quarters — were by Albanians.

The NAO report revealed that many of these ‘withdrawals’ were actually what lawyers call non-compliance refusals: the asylum seeker failed to return a form on time, did not turn up to an appointment or something like that. Some asylum seekers may genuinely have deliberately disappeared. But experience suggests the Home Office is bad at logging changes of address, posts things to the wrong address anyway and that a certain proportion of these decisions will turn out to be wrong.

This creates two problems. One is that many of those treated as ‘withdrawn’ will still be in the UK and will resurface. They may lodge a judicial review of the non-compliance refusal if they think it was a mistake by the Home Office or otherwise will renew their asylum claim or make a new one. They will become complex cases and will take additional resources to process. The Home Office may be making more work for itself in the long run by trying to hit its short-term targets. This would be entirely typical behaviour by the department.

The second problem is that the level of supposed ‘decisions’ is therefore unlikely to be sustained given that only 12,000 or so Albanians arrived last year. If we put withdrawals to one side, the number of actual, proper decisions fell in the first quarter of 2023:

If we put withdrawals to one side, the number of actual decisions fell in the first quarter of 2023. The spike in resettlement cases in 2021 Q3 represents the Afghan evacuation. You can see for yourself how refugee resettlement work has fallen off since then.

There’s lots wrong with our asylum, immigration and citizenship laws. If you want to be properly informed, check out my book Welcome to Britain, now available in paperback.

Asylum outcomes

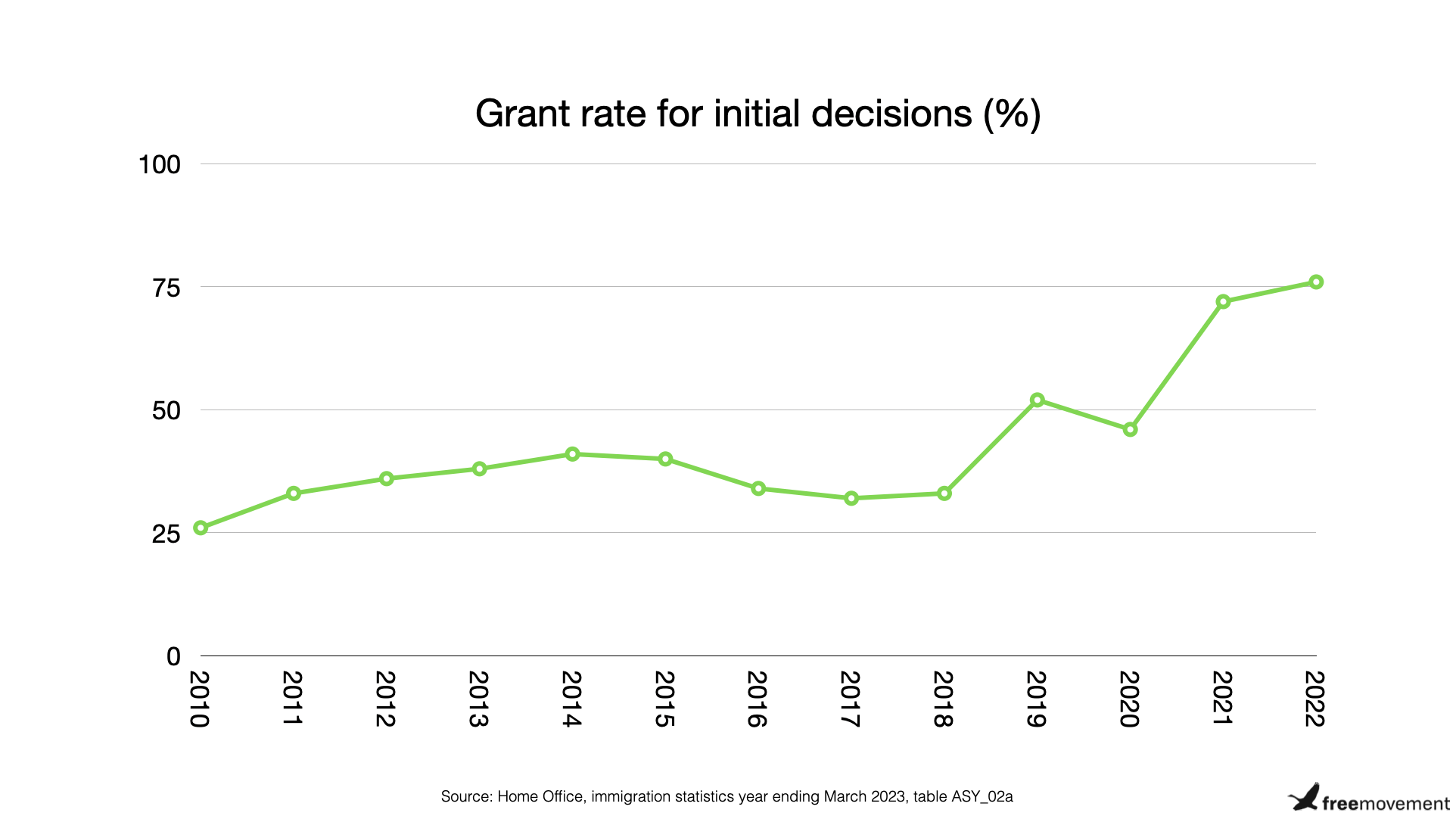

In the year ended March 2023, 74% of initial asylum decisions by the Home Office were grants of protection. That is an historic high not seen since since the 1980s, when there were far fewer asylum claims being made.

However, the figure may have now peaked; there was a one percentage point fall compared to the year ended December 2022. This might well reflect the changing demographics of those claiming asylum. There has been an increase in claims by Albanian men and Indians, who have relatively low success rates compared to other major nationalities:

- Afghanistan: 98%

- Eritrea: 99%

- Sudan: 83%

- Syria: 99%

- India: 5%

- Albania: 34%

The Albanian success rate is down from around 50% before the spike in Albanian claims in 2022. Before that spike in Albanian claims, a far higher proportion of Albanian claims were made by women; the majority of Albanians arriving in 2022 were men and Albanian men have always had a lower success rate than Albanian women.

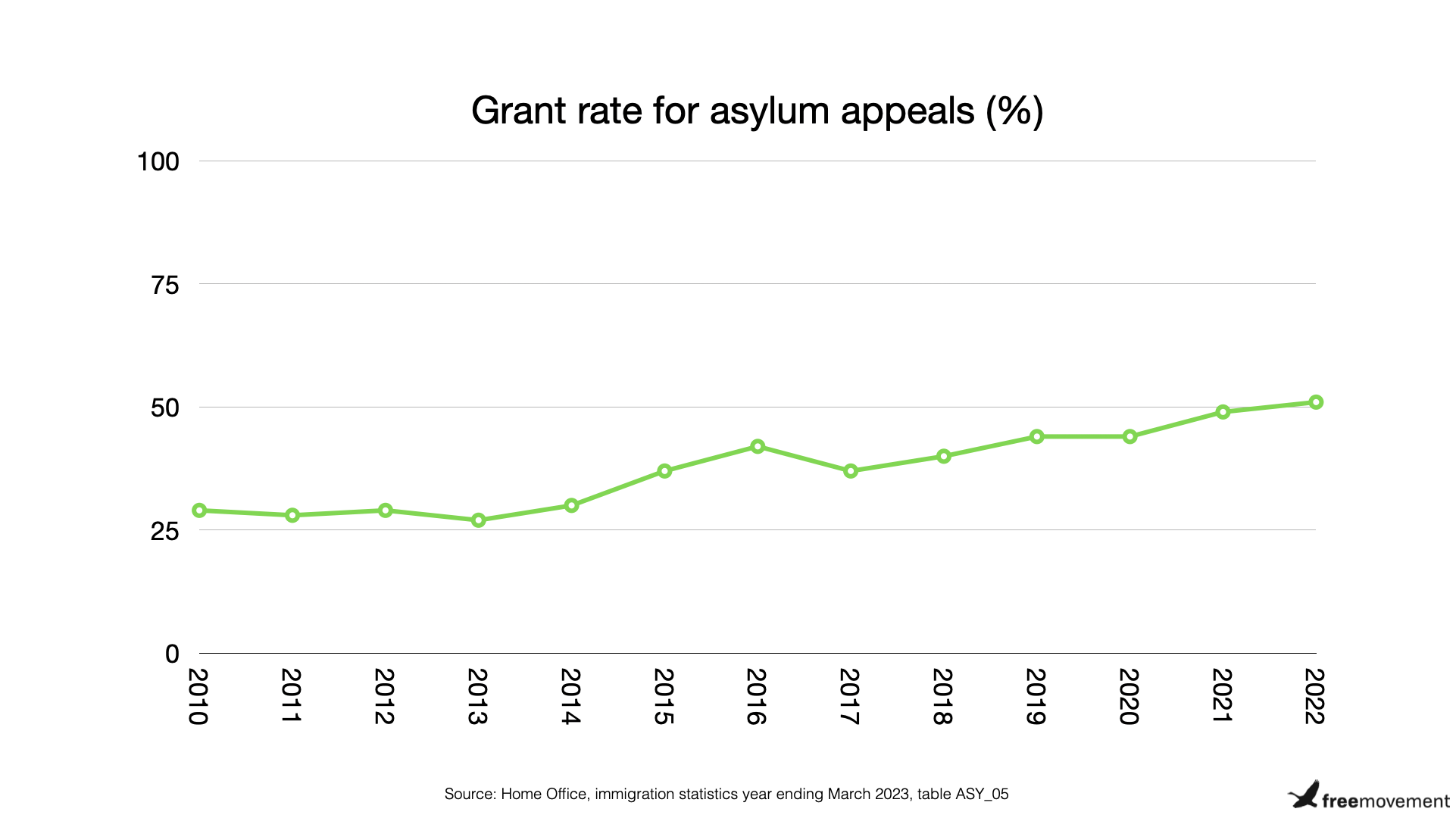

Not only that, but some of those asylum seekers refused protection by the Home Office will go on to win their appeals. We might expect the appeal success rate to fall somewhat as the initial application success rises but there is no evidence of that happening yet.

The average time it takes for the First-tier Tribunal to decide an asylum case was 82 weeks in the period April to June 2023. This is up from 29 weeks prior to the pandemic. It was only 48 weeks as recently as 2021, so this looks like a pretty serious problem at the tribunal. Given that it is well known that there is a huge asylum backlog and that the Home Office is increasing the number of asylum decisions made, it was inevitable that the asylum caseload at the tribunal would increase. It seems this has not been matched by increased resources for appeals.

Detention

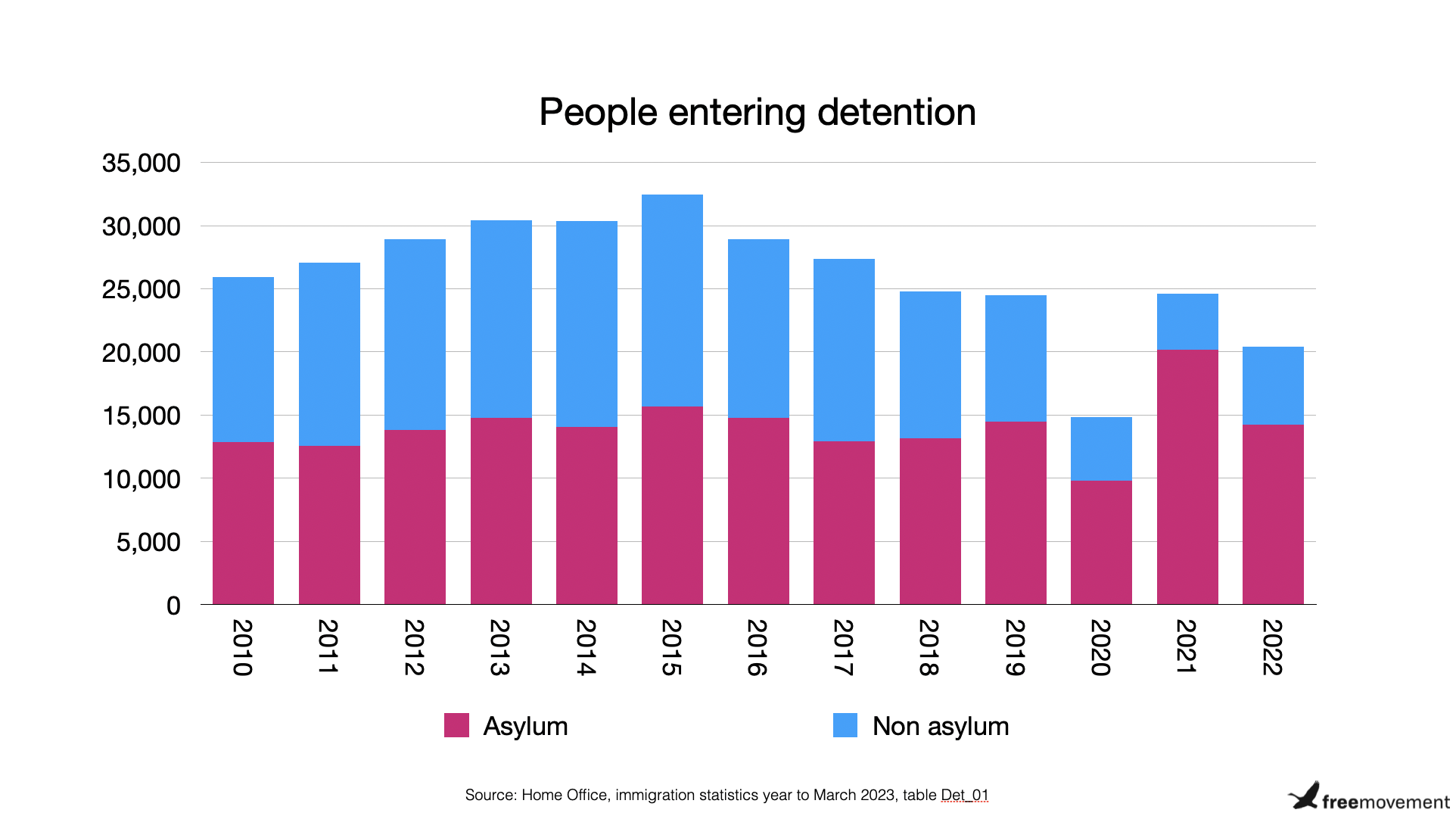

Use of immigration detention has decreased in recent years. A the same time, the percentage of those experiencing immigration detention who are asylum seekers has increased markedly.

These figures do not include those detained at the de facto detention camps at Penally and Napier barracks, from which asylum seekers were allegedly free to come and go.

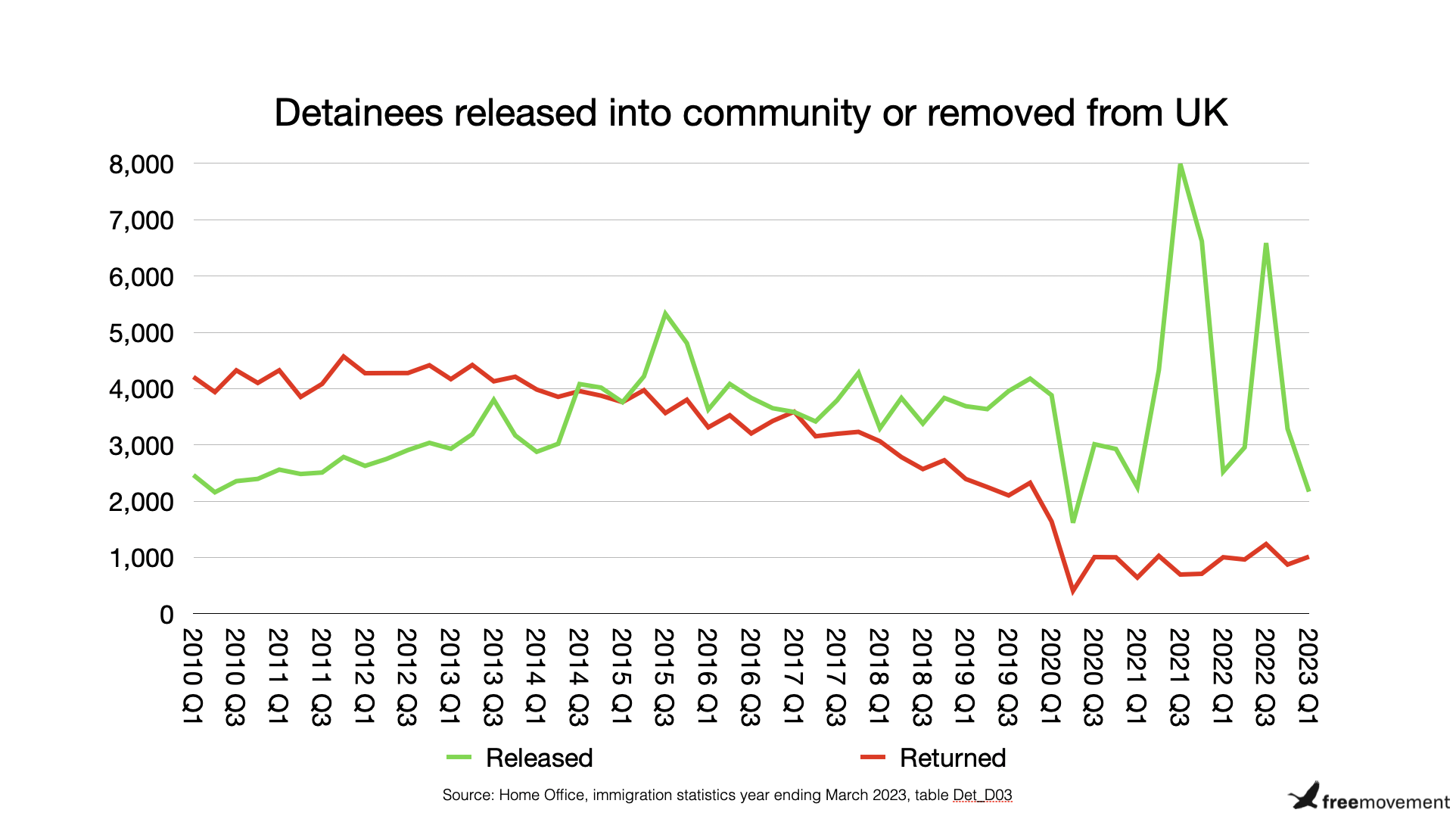

Immigration detention is supposed to be for the purpose of removing those with no permission to remain in the United Kingdom. Immigration detention centres are formally called ‘removal’ centres. However, the number of detainees leaving detention to be removed from the country has fallen drastically since 2010. The majority are now released into the community.

This calls into question whether a decision to detain these people was the right one. The cost of holding a person in immigration detention is around £90 per day.

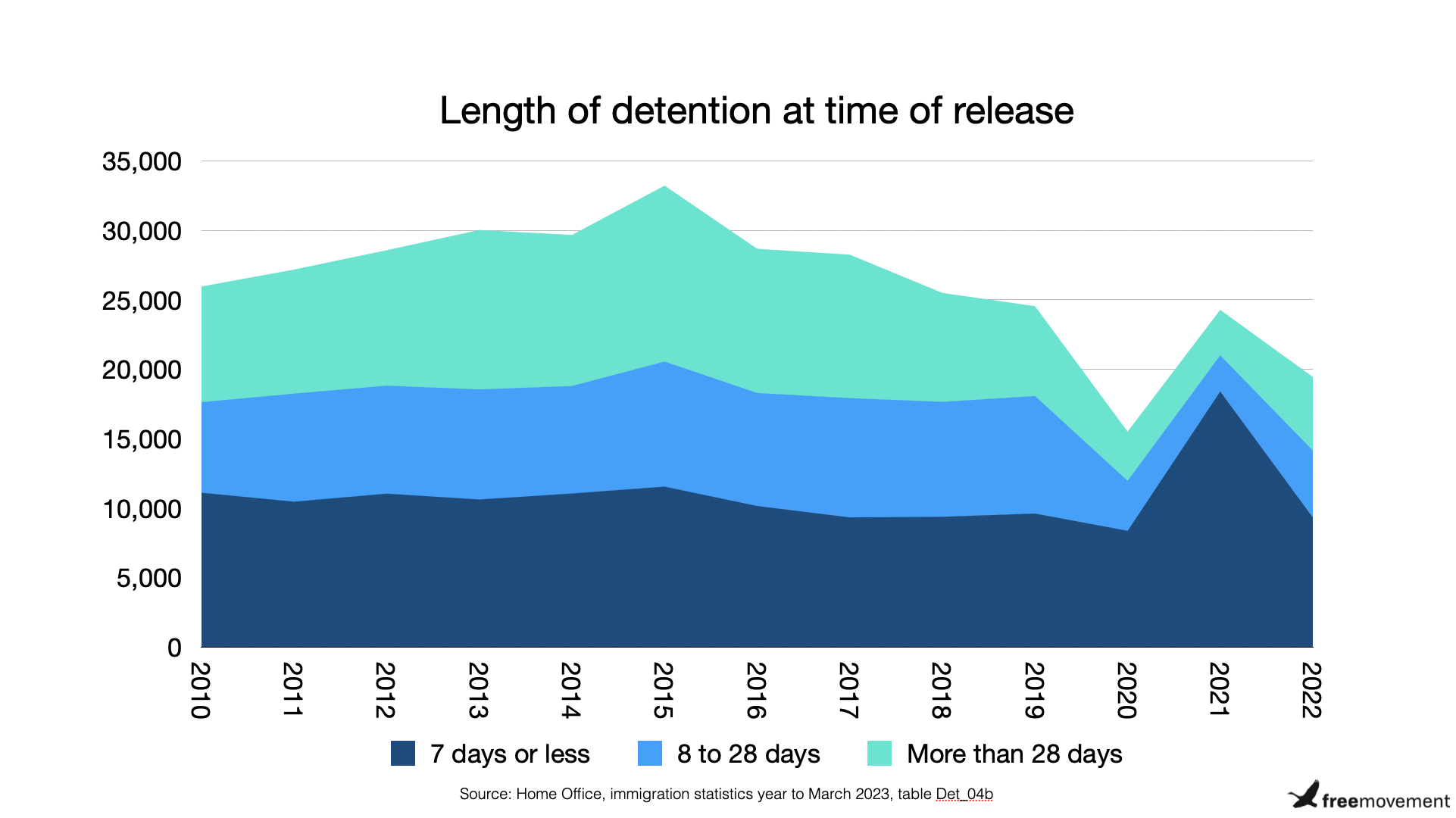

Substantial numbers of people experience fairly short term detention and some experience prolonged detention.

The percentage of people held in short term detention increased markedly in 2021 and then fell back again in 2022. It seems reasonable to assume many of these individuals were asylum seekers given that the number of asylum seekers experiencing detention increased at the same time (see above). Their detention certainly does not seem to have led to faster decisions or to more removals so, again, the purpose of detaining them is unclear.

Removals and returns

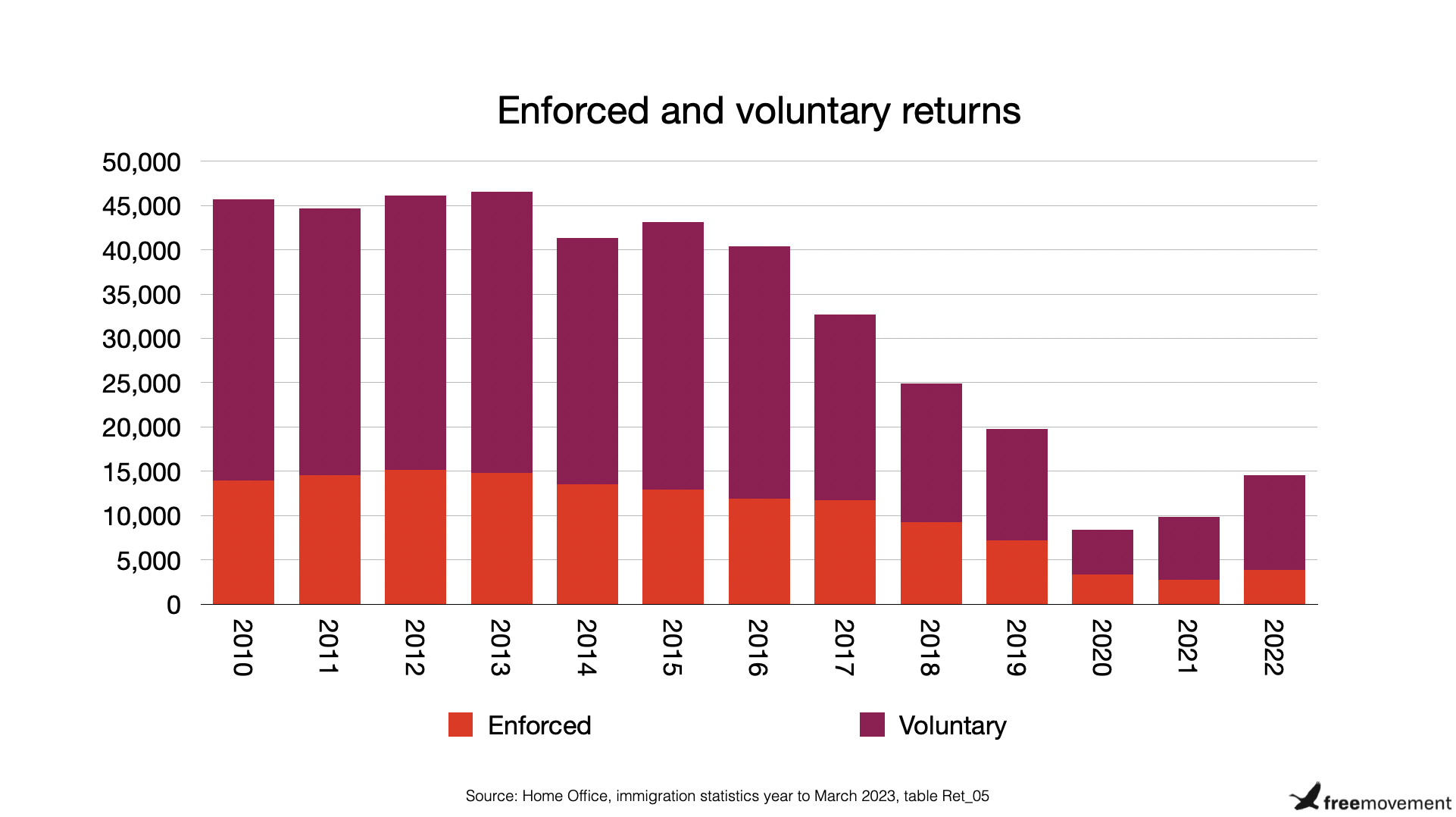

Very few asylum seekers have been removed or voluntarily departed from the UK in recent years. First of all, we can see from the overall numbers that there has been an overall decline for all enforced removals and voluntary departures. This includes foreign national offenders, overstayers and former asylum seekers:

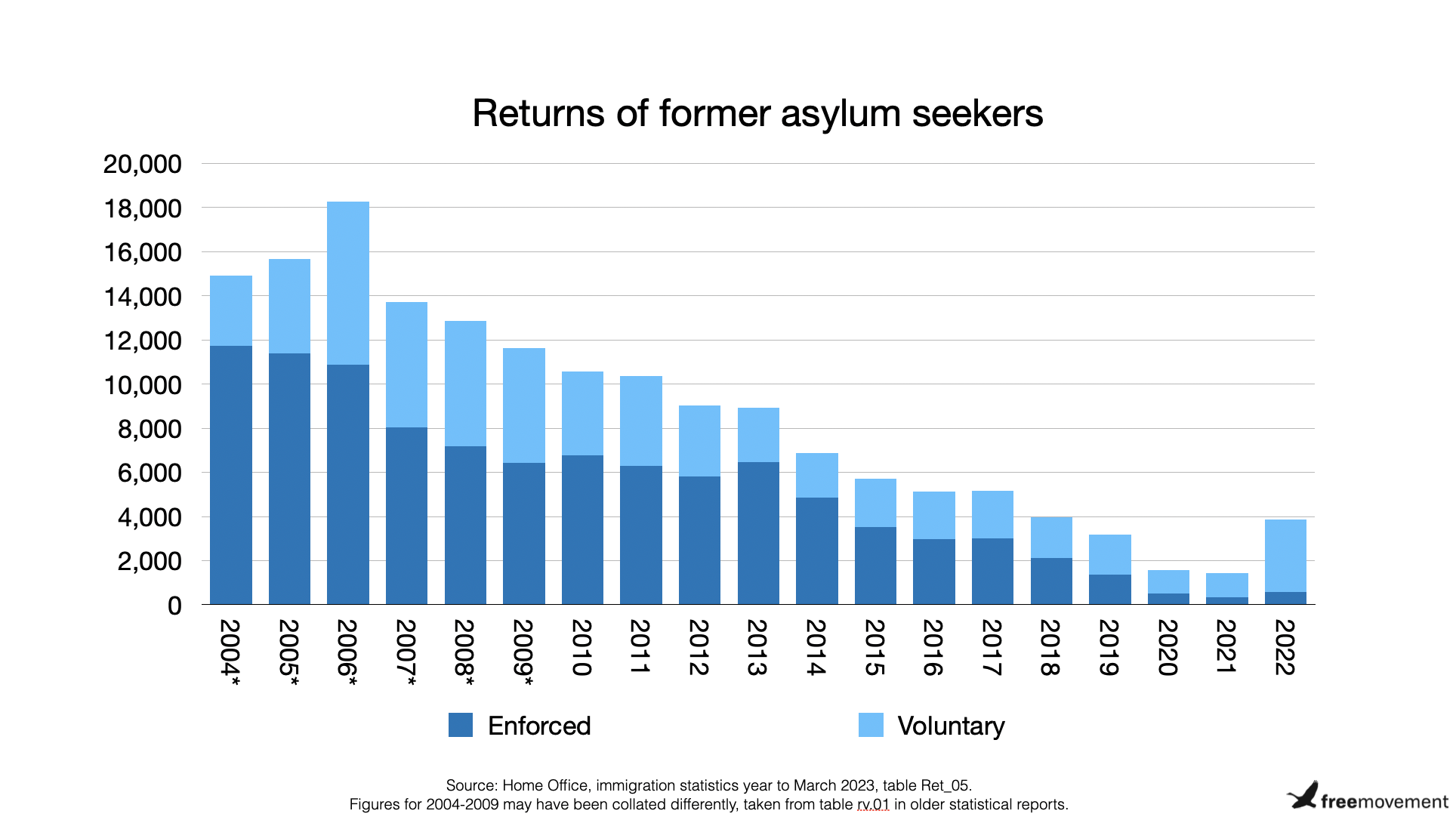

Once former asylum seekers are separated out, we can see that only a very small number are being removed: just 336 enforced asylum returns in the whole of 2021 and 580 in 2022.

The reality is that even those who lose their asylum cases — an increasingly small minority given the rise in the grant rate — are likely to remain in the United Kingdom in the long term. If you don’t believe me, see the returns summary tables, table Ret_05.

Resettlement

The government likes to talk about safe and legal routes to reach the United Kingdom. The reality is that unless you are Afghan, Ukrainian or from Hong Kong there are no such routes.

In the year ended March 2023, 3,452 refugees were resettled through Afghan schemes but just 711 through the wider UK resettlement scheme.

Remember: there is no queue to jump. It is not possible for a person to apply for the general resettlement scheme. Eligibility is determined by UNHCR. Essentially, a person has to be a registered refugee in a UNHCR administered refugee camp and hope they are picked for resettlement. If they are selected, they have no say over the country to which they are resettled. It might be the UK but it might be Australia, Canada, the United States or other participating countries.

The good news is that as May 2023 a total of 175,800 Ukrainians had entered the UK under the two visa routes opened for them. Some will also have returned home in that time. You can see the latest statistics yourself here. Many more visas than that had been issued but not yet used. UNHCR have put together data on which countries are hosting how many refugees. By way of comparison, Poland is estimated to be hosting 992,670, Germany over 1 million, Czech Republic 341,745, Bulgaria 160,575, Spain 182,600, Italy 175,105 and France 70,570.

A total of 140,776 visas have been granted to British Nationals (Overseas) from Hong Kong and their dependants. While this can be classed as a resettlement or protection route, the vast majority are not refugees according to the legal definition of a refugee and many would reject that label.

What can be done?

The United Kingdom asylum system is indeed broken. It is, to a very significant extent, Priti Patel who broke it. It was on her watch that small boat crossings soared and so did the asylum backlog. The asylum backlog was already growing when she took over but she has allowed it to triple further on her watch. Schemes like a new 10 year route for refugees, recently abandoned, and increasing the Home Office resources funnelled into pointless age disputes made the situation worse not better.

Ministers and managers need to think about prioritising resources. This has to mean doing less of some things in order to do more of others.

But the asylum system is not beyond repair. All it requires is competent focus on the boring day job instead of being distracted by pointless gimmicks. There is a danger the Illegal Migration Bill will actually make things worse, as I argued in a previous post. The idea that the Home Office is going to remove all of the 84,000 people they expect to be in the new backlog by the end of 2023 plus all those who newly arrive is preposterous. They will either have to be supported by the state in the meantime or they will disappear, given they will no longer have any prospect of ever been granted asylum and therefore no incentive to remain in contact with the Home Office.

Asylum decisions need to be made much, much faster. It’s just not that hard to grant asylum to an Afghan, Eritrean, Sudanese or Syrian given they have a 98% grant rate or more. All they need to do is to establish nationality, conduct security checks and issue the grant letter. The Home Office seems to have messed even that up by issuing long, complex forms in English only and failing to fund any help to fill them in. Absurdly, after we warned them it was a bad idea, they decided to blame the lawyers. Again.

If we step back and look at the fundamental change in the asylum grant rate combined with the low number of asylum removals and departures, we can see that it is time to scrap the deterrent policies established in the 1990s and early 2000s, when far fewer asylum claims succeeded. Michael Howard, then Home Secretary, told Parliament in 1995 that only 4% of asylum succeeded as did a further 4% of appeals. The ban on the right to work, the destitution-level support offered instead, the squalid accommodation and camps and the highly bureaucratic, faceless asylum process all absorb vast Home Office resources to administer. These policies, which belong to a bygone age, deter no-one. They merely serve to punish genuine refugees who will ultimately get to stay in the United Kingdom in the long term. It is their interests and ours to help them integrate as soon as possible rather than forcing them into this demeaning purgatory first.

Want to really get to grips with refugee law? Concise and readable, Colin’s textbook walks you through everything from well-founded fear to refoulement.